From Diagnosis to Medical Oncology

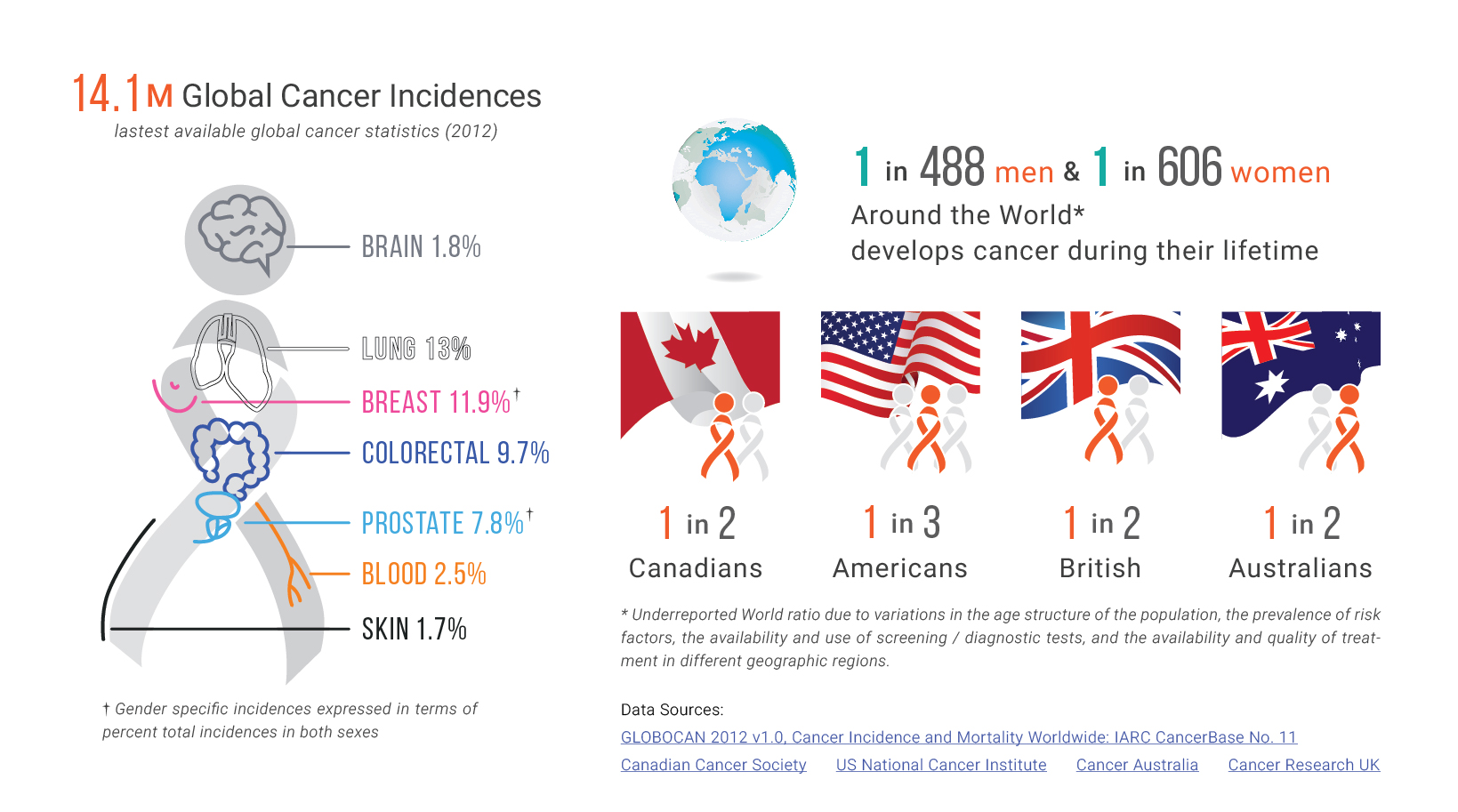

The cancer care continuum begins at screening and diagnosis and continues onto treatment. Some cancer types— such as skin, breast, and prostate— may be detected by routine self-exams or other screening measures. Cancer may also be diagnosed incidentally when investigating or treating other medical conditions. Further examination is required when abnormalities are noticed by either the patient or a healthcare professional.

This investigation involves a thorough physical exam and is enhanced with laboratory studies. When the presence of a tumor is suspected, imaging tests, such as X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and endoscopy examinations are ordered. In the final step, to confirm diagnosis, a biopsy is performed in which a tissue sample is removed and studied to identify the presence of cancer cells. These actions help the physicians and the care team determine the cancer’s stage, location, and size.

It is generally during the diagnosis stage that physicians – primary care doctors, gynecologists, dermatologists and others – refer suspected or confirmed cancer patients to oncologists. As cancer is complex, its treatment often requires a mix of therapies in addition to lifestyle changes. Depending on the type and stage of cancer, the patient may need a special type of oncologist, or even more than one kind. There are three basic types of cancer treatment doctors [1]:

1) Medical Oncologists

2) Surgical Oncologists

3) Radiation Oncologists

Throughout the duration of the cancer care continuum, patients may go through a combination of treatments to slow tumor growth or eradicate it. It is the cancer and treatment type that will dictate the patient’s main doctor. The relationship built between the cancer care doctor, care team, and patient will most likely last through treatment and into survivorship.

In this article, we will focus on the scenario that the care team recommends systemic therapies – such as chemotherapy or immunotherapy – to get rid of cancer cells. We will explore the role of a medical oncologist in providing care along with the latest innovations in medical oncology.

Medical oncologists are a core member of the cancer care multidisciplinary team, and offer cancer patients a comprehensive and evidence-based approach to treatment and care. They aim to use safe and cost-effective cancer drugs, while maintaining the quality of life of cancer patients throughout the cancer journey. Contributions of medical oncologists are essential in integrating information, at all levels and settings.

For most referrals of suspected or confirmed cancer cases to a medical oncologist, the patient is unsure whether they have a malignant tumor. Understandably, when patients learn that they might have cancer, they want to ensure that they receive the best possible care and treatment. Therefore, good communication and effective patient engagement strategies will facilitate the transmission of realistic information.

It then becomes the oncologist’s role to manage a patient’s care throughout disease. This includes:

- Explaining the cancer diagnosis and stage of cancer

- Talking about all treatment options – may be one or a combination of oncology specialty treatment options – and the preferred option for the patient

- Delivering continuous quality and compassionate care throughout all phases of care

- Assisting with symptom management and

Medical oncologists aim to treat cancer using systematic approaches, which target the entire body. Based on the type and stage of cancer, the medical oncologist may suggest one or a few treatment options [2]

1. Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the traditional anti-cancer therapy. Chemotherapy drugs circulate throughout the bloodstream and disperse to destroy cancerous cells in multiple locations. Due to its nature, chemotherapy is often used to treat cancers that have spread beyond their original point of development.

Chemotherapy is a useful approach for: treating cancer, keeping cancer from spreading and slowing the growth of a tumor. In most cases, chemo increases survival time. Nevertheless, it is accompanied with acute and insidious side effects. Colon and breast cancer tumors have seen an improvement in survival using chemotherapy, but these benefits have to be weighed against the impact of persistent symptoms such as fatigue or neuropathy [3]. In addition, a significant proportion of cancer patients suffering from cancer types, such as melanoma and renal cell carcinoma, may not respond to chemotherapy or relapse after treatment. For these cancers, patients have received minimal benefit but significant toxicity

2. Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy – also called biotherapy – uses biologic agents, concentrated amounts of the body’s natural substances, to boost the immune system to fight cancer cells. The immune system is the body’s defense mechanism. When it detects a threat or abnormal behavior, it reacts. This is called the immune response. At times, the immune system is not strong enough. This is where immunotherapy enhances the actions of the immune system to fight cancer cells.

Kames Allison, of the United States of America, and Tasuku Honjo, of Japan, won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine for pioneering this ground-breaking cancer treatment approach [4]. They laid the foundation for the development of a number of medicines now approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat cancers.

In 2011, the FDA approved ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 antibody, as a treatment for late-stage melanoma. This drug results in the stimulation of an immune response against melanoma. Even though, there are still a handful of side-effects that need to be monitored by the cancer care team during and post-treatment.

Vaccines, medicines that can train the immune system to recognize and destroy unwanted substances, are being utilized to prevent and treat cancers. With regards to cancer treatment vaccines, it may prevent the cancer from recurring, destroy any cancer cells still in the body after other treatments have ended, or stop a tumor from growing or spreading. Researchers are currently testing vaccines for several types of cancers in clinical trials, including breast, cervical, and prostate cancer.

3. Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy uses drugs, and in some cases surgery, to stop cancer cells from growing. This treatment method works in two ways:

1) Prevents the production of abnormal hormones that can cause cancer;

2) Alters the actions of hormones.

Hormones are produced by many glands in the body, and act as the body’s chemical messengers. They travel throughout the body to regulate the activity and behavior of cells and organs. In women, estrogen and progesterone, produced by the ovaries, play a role in a woman’s reproduction functions as well as sexual characteristics, which can also trigger the growth of breast cancer.

In men, testosterone and dihydrotestostrone, produced by the testicles and adrenal glands, play a role in regulating a man’s sexual development and function. When too many of these hormones are made, prostate cancer may occur.

Hormone therapy uses synthetic hormones or drugs to disrupt the action of the body’s natural hormones. It aims to stop the flood of hormones to the affected tissues and prevents the cancer cells from growing.

The type of hormone therapy used is unique to the cancer type. For instance, a form of treatment for breast cancer may require Tamoxifen, which is a drug that blocks the receptors on the breast cancer cell. This blockage prevents estrogen from binding to cancer cells. Hormonal therapy in breast cancer has improved disease free survival by 10% in 10 years [5]. Similarly, for prostate cancer, there are several types of hormone therapy measures used to treat prostate cancer, including surgery that removes the testicles. As surgery is a permanent treatment, many patients may resort to medical castration, using drugs to lower the amount of hormones made by the body [6].

4. Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies use drugs to interact with cancer cells by targeting specific molecules, such as genes and proteins, involved in cancer growth and spread. These therapies are different from traditional cancer drugs used in chemotherapy, which act on all fast-growing cells. As oncologists are able to match targeted treatments to the patient’s tumor characteristics, these therapies may work more effectively, with fewer side effects. Our previous article explores targeted therapy as a precise method of fighting cancer with drugs.

It is clearly evident in our exploration of the field of medical oncology and its main systemic therapies that this field has made incredible advances and will continue to evolve. With strategic collaboration and documentation of information at all levels of care, shortcomings can be alleviated.

In our next article, we will explore non-systemic therapies in the fields of surgical and radiation oncology, and discuss how the continuous emergence of health technologies is confronting the growing cancer burden worldwide.

Written by Dorri Mahdaviani , who holds a Masters of Public Health (MPH) from the University of British Columbia (UBC). Her academic and professional interests include the areas of chronic illnesses, health care systems and childhood health and development.