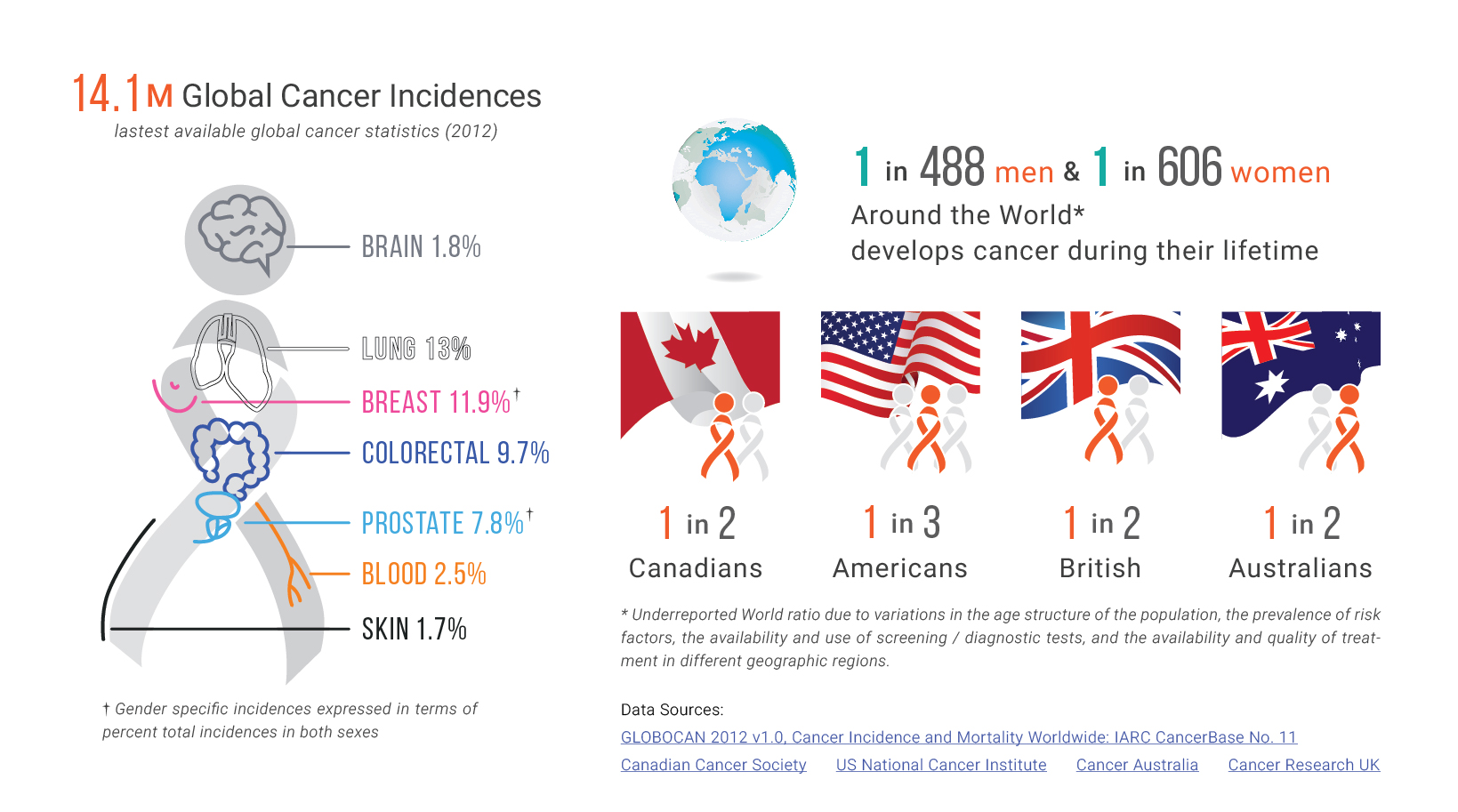

Importance of Continued Cancer Screening during a Global Pandemic

There is no denying cancer screening transformed cancer care, as it aims to detect cancer before the appearance of symptoms. Timely screening has proven to be an effective tool in early diagnosis and decreasing cancer mortality rates. With early screening and engagement, health professionals are able to connect with patients sooner and tailor treatment plans to individual screening results and tumor characteristics, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes.

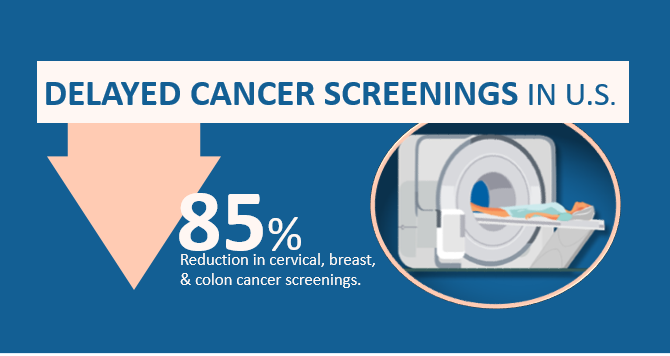

This initial step in cancer care has been dramatically altered due to the global pandemic. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in the United States have classified screening as a low-priority service and suggest healthcare organizations to consider postponing screenings. Many patients are also fearful of exposure to the COVID-19 virus or of overburdening healthcare services and thus have been less likely to present to healthcare services for cancer screening and diagnosis. As a result, the number of tests to screen for cervical, breast and colon cancer fell by 85% or more after the first COVID-19 cases was diagnosed in the U.S..

Cancer progression has not paused, and the impact of delayed screening may be drastic. The dip in the number of screenings is concerning as it jeopardizes our ability to diagnose disease early. It will also become more challenging for health systems to recover quickly and resume screening and diagnostics the pandemic intensifies and continues over time.

As the world is still in the midst of a global pandemic, healthcare administrators and systems, need to plan and adapt to allow patients to receive regular screening services in a way that minimizes community spread of COVID-19. For instance:

- COVID-19-free facilities should be ideally located in sites separate from acute-care hospitals

- If it is not possible to geographically separate COVID-19 facilities and cancer-care facilities, separate spaces should be designated in mixed-care sites, with dedicated access and admissions processes for patients with cancer

- Cancer care services should be delivered by a designated team of providers to reduce the risk of exposing COVID-19-free patients and healthcare workers to the virus

- Patients should be screened with strict rules of admitting, such as only allowing patients with no symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, have self-isolated for 7–14 days, and/or have tested negative for COVID-19 test. Staff at facilities could be trained to screen patients prior to scheduling appointments and at the time of appointment

It is also important to develop a program of testing and triaging to determine which patients require immediate screening on the basis of clinical need. This may require rescheduling of non-essential follow up visits or diverting these visits to telemedicine if available. Visits past the five-year mark for patients with no evidence of disease or concerning symptoms should be considered for rescheduling when clinical, laboratory, and imaging reports suggest low risk for recurrence.

These changes to screening will require active monitoring of waiting lists, communication with patients remotely, and enhanced communication between providers and facilities. Screening for cancer is a process that involves many moving parts, from primary care clinics, hospitals, and imagining facilities. Health systems will need to adopt new technologies to engage with patients and healthcare teams in a centralized and coordinated manner. As a leading provider of comprehensive care coordination solutions, Equicare Health can facilitate this process. Equicare Health’s platform bridges the gaps and seamlessly connects health professional team members to each other and their patients

For instance, lung cancer screening programs have been altered during the COVID-19 pandemic as the risks from potential exposure to COVID-19 and resource allocation that has occurred to tackle the pandemic. This has altered the balance of benefits and harms of screening. Performing a screening examination, and the evaluation of lung nodules, now carries an added risk. To date, health providers and hospital systems have been independently determining how to modify their screening and nodule management programs during the pandemic. For jurisdictions that are of low risk of COVID-19 transmission, Equicare Health’s standardized follow-up template to track lung screening patients and collect data that can be uploaded to the American College of Radiology (ACR) Lung Cancer Screening Registry may be an advantageous tool to minimize the risk of virus transmission.

Additionally, Equicare can help enhance communication with patients and increase their engagement in their care journey through the patient portal. The portal allows patients to connect directly with their care team. For example, patients can respond to electronic questionnaires to facilitate triaging of care. Once in the portal, patients can access individualized information, such as their test results, educational material, as well as their telehealth appointment schedule. Regular visits to the portal will help patients and their caregivers keep up-to-date on the progress of their journey and maintain contact with their care team without physically visiting a healthcare site. This can improve the experience of care for both patients and providers, and helps facilitate the continuation of cancer screening during this global pandemic.

Written by Dorri Mahdaviani , who holds a Masters of Public Health (MPH) from the University of British Columbia (UBC). Her academic and professional interests include the areas of chronic illnesses and health systems.